Your Time, My Time

~ A Short Story by Allen Kopp ~

(This short story has been published in The Literary Hatchet.)

Severin Dinwiddie was eleven when his family moved into a different house. And a big house it was, with six rooms upstairs, seven downstairs, a spacious attic and a basement divided by concrete walls into separate little rooms.

Severin was an only child and, since he had always liked being alone, the house was perfect for him. There were more doors in the house than he had ever seen, and they all led to interesting places, sometimes into other rooms and sometimes only to other doors. The ceilings were high and the rooms dark. The attic, reached by steep wooden steps, was cavernous and shadowy, lit by a single bulb that hung down from the ceiling. In the kitchen was a dumbwaiter that was no longer used and a dark, narrow staircase that went down into the basement. It was a house, it seemed, that held secrets of its own and that might even harbor a ghost or two. If there were ghosts, Severin was sure to see them.

It was a house in which Severin might be absorbed and forgotten. His father was gone most of the time, a traveling businessman, and his mother was so wrapped up in her fat self that she forgot from time to time that she was a mother. She was enormously obese, called herself an invalid, and once she had installed herself in the master bedroom upstairs, seldom left it. She had a “girl” to wait on her and bring her her medicine or food from the kitchen. The girl’s name was Karla. She used to work as a bouncer in a nightclub and had spent some time in women’s prison. She had tattoos on her arms and a mustache. Severin avoided her. Whenever he saw her, he ran the other way as if she was a cat and he a mouse.

When Severin played his old-time jazz records, his mother complained.

“Nobody listens to that kind of music, you little freak!” she railed.

He needed a place where he could feel free, at least where he could do what he wanted and be left alone. That’s when he began spending a lot of time in the basement.

In the corner of the basement, underneath the stairs, was the perfect space for a small boy to do as he wished. He set up his card table, brought his record player and a few records down, along with a comfortable chair, a couple old quilts to make a pallet on the floor, a few books, and sundry other items. Luckily there was an electrical outlet nearby for him to plug in his record player and an old floor lamp he found that was left behind by the former resident.

Right away he felt safe and secure in the space under the stairs. His mother wouldn’t be bothered by his music, no matter how loud he played it, and he didn’t have to worry about running into Karla. As for his father, there was no chance he’d bother him because he was never home.

Severin tried to think back to the last time he saw his father and couldn’t remember how long it had been. Where was his father now? He might be anywhere in the world, flying in a jet above pink clouds or getting ready to go to bed in a hotel room in some strange, foreign city.

And no matter how many hours Severin spent in the basement—listening to music, reading, napping, or just thinking—his mother never seemed to realize he was gone. She never asked where he had been or how he had spent his day. In fact, he hardly ever saw her. At suppertime, he went upstairs to the kitchen, where he would find a sandwich, some fruit, or a bowl of soup that Karla had left there for him.

After he ate, he would go upstairs to his room and get ready for bed, lingering for a few seconds outside the closed door of his mother’s room, where he would hear her television or the low murmur of her voice as she spoke to Karla. He didn’t much like his mother and didn’t feel any special connection with her. If she died, he wouldn’t feel very sad, except that his father would probably put him into some kind of a children’s home because he didn’t know how to be any kind of a real father. Severin looked forward to the day when he was old enough to leave them.

One afternoon, after he had spent all day since breakfast in the basement, he went to sleep on his pallet on the floor. When he woke up, he noticed a trap door in the ceiling above his head that he had never noticed before. Where did the trap door lead? He wasn’t going to be able to put it out of his mind until he found out.

Standing on the card table, Severin found he could just reach the trap door. He pushed it and it opened easily. There were footholds and handholds enough that he was able to pull himself all the way through. When he stood all the way up, he saw he was standing in the kitchen, but it wasn’t the same kitchen. It was the same, but somehow different. To begin with, the refrigerator was different, the stove, the kitchen sink and the linoleum on the floor. The most striking difference, though, was that four people were sitting around a table: a father, a mother, a son and a daughter. He didn’t know who they were and had never seen them before. The father had a bald head; the mother was a blonde; the girl was about nine and the boy about thirteen.

Severin was confused but mostly he was embarrassed that he was intruding. They were having dinner and they wouldn’t like it that he, a complete stranger, was in their house. He couldn’t explain it even if he tried. He didn’t know what to say to them, but he believed he should say something.

He approached the table. The four people were eating and talking. When he stood close to them, he could see their mouths moving when they spoke, but their voices were muffled and he couldn’t understand what they were saying. It was as if something had suddenly gone wrong with his hearing.

“Hello!” he said, thinking they would all look at him in surprise, but they went right on eating and talking and didn’t look at him at all.

“I’m sorry to be in your house this way,” he said, “but I thought I was in my own house and I don’t know how I got here. I know that sounds crazy, but…”

He stopped talking when he realized they couldn’t see him or hear him and didn’t know he was there. He must be having a dream, he thought, but if it was a dream it was the most realistic dream he ever had.

He went back down through the trap door into the basement, dropped down onto the card table, and went to sleep again on the pallet on the floor.

He didn’t think about the four people again until, asleep in his room in the middle of the night, he woke up and remembered them. No matter how much he thought about them and tried to remember, he didn’t know who they were or where they came from. Did he just think them up out of his imagination? Were they out of a book he read or a movie he saw? Were they ghosts?

The next afternoon, in his basement hideaway, he was going to forget about the trap door, but his eyes kept going up to it. Before he knew it, he was standing on the card table, shimmying his way through the small opening again.

The house was still, as if nobody was at home. He stood quietly in the kitchen for a minute or two and heard nothing. When he was reasonably certain no one was there, he proceeded into the living room and dining room.

Those rooms were the same rooms he was familiar with, but everything else was different: the dining room table and chairs, the sideboard, the couch and overstuffed chair, coffee table, lamps, pictures on the walls, rugs on the floor. All the furniture was neat and straight, everything in its proper place. There was no television, though. (What kind of a family didn’t have a television?)

He went upstairs, his feet sounding too loud on the treads. He didn’t think there was anybody at home, but if he did happen to meet one of them, he would try to explain (explain what?), or he would turn around and run and hope he wasn’t seen.

He made a circuit of all the upstairs rooms, checking the bathroom and each one of the bedrooms. All the bedrooms had beds in them and other furniture he had never seen before. His own bedroom was the same room, of course, but his bed and chest-of-drawers were gone and in their place furniture he had never seen before. He opened the closet door and saw his clothes were gone and somebody else’s clothes in their place.

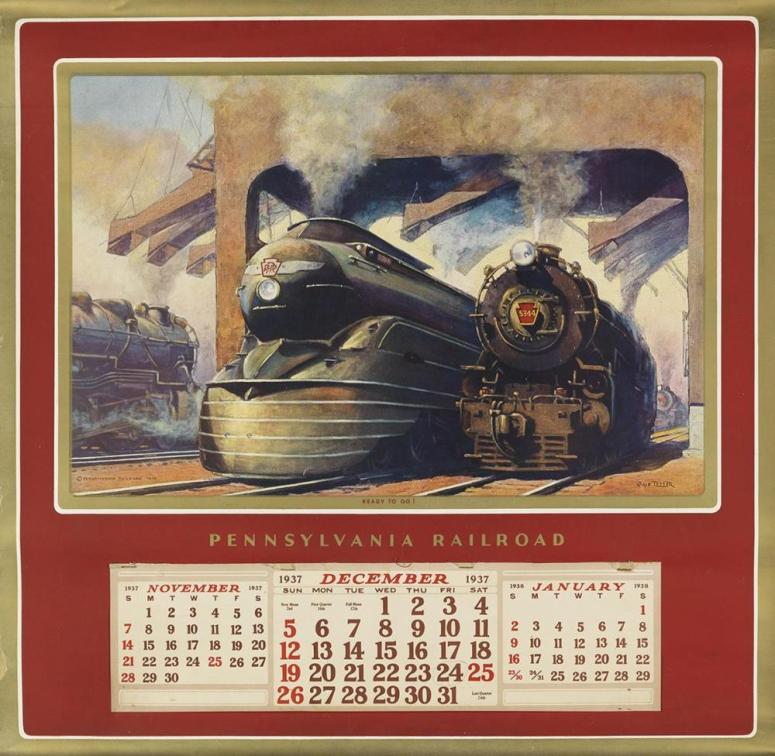

Believing he heard a door opening downstairs, he crept back downstairs, through the living room and into the kitchen. He was making for the trap door, when he saw, hanging on the wall, something that stopped him in his tracks: a calendar showing the year 1937. He didn’t know much about history, but he knew that 1937 was a long time ago. That would explain why there was no television in the house. Nobody had televisions yet in 1937. Also, that would explain the old-fashioned furniture and drapes and all the rest of it. These people, whoever they were, were from a long time ago, but they were living in his house, or what seemed like his house.

He went back down through the trap door and into his familiar basement hideaway. Out of breath, he sat on the floor with his back against the wall, having the feeling that he had just barely escaped. He had been in somebody else’s house and they were going to come after him. He had seen things he wasn’t supposed to see. Something bad was going to happen if he wasn’t careful. He would never go through the trap door again. He would put it out of his mind.

But he wasn’t able to put the trap door out of his mind. He kept thinking about it again and again. He woke up several times in the night thinking about it. He woke up in the morning thinking about it. The trap door was inviting him to climb through.

And climb through it he did, right after lunch. Since it was Saturday, all four members of the family were at home. The mother was in the kitchen baking a cake; the father was in the living room reading a newspaper. The son and the daughter were nowhere to be seen, probably upstairs in their rooms.

Feeling bolder now, Severin walked up to the mother in the kitchen and stood three feet away, where she was sure to see him. She didn’t see him, though, but went right on mixing her cake. When he went into the living room and stood in front of the couch, the father went right on turning the pages of the newspaper and didn’t look up, even when Severin made little popping sounds with his mouth. That’s when it occurred to Severin that maybe he was the ghost and not them.

Just then the little girl came down the stairs and said something to her father. Severin stood right in front of her where she would be sure to see him, but she walked right past him and went into the kitchen. He had never felt invisible before and found it a most agreeable sensation.

After that Severin began visiting the family every day. In time, he learned their names. The boy’s name was Gunner and the girl’s name was Phoebe. The mother was Marcella and the father Clyde. Their last name was Pettibone. Clyde Pettibone taught history in high school.

After six or eight of these silent and anonymous visits, Severin began to feel more comfortable with the Pettibone family. He sat with them when they were eating or listening to the radio and he had to admit he liked them. He listened to their talk and their laughter and he saw how free and easy they were with each other. There were no temper tantrums, arguing, tears or hurt feelings—all the things he was accustomed to with his own family.

On one of these visits, the mother looked directly at Severin, smiling, and said, “We hear your music.”

Her voice still sounded to him like a voice under water, but her smile told him she didn’t disapprove of old-time jazz.

A few days later she asked him if he’d like to stay and have dinner with them. He nodded his head and she set him a place at the table.

She put the food on a plate in front of him. He saw the food, picked up a fork and tried to eat it, but by the time he put the fork to his mouth, the food had disappeared because for him it didn’t exist. He tried to pretend he was eating when he wasn’t, but he didn’t think he was very convincing.

On succeeding visits, Phoebe and Gunner were able to see him, and then when their father came into the room, he acknowledged that he could also see him.

“Where do you come from?” Phoebe asked. “We haven’t ever seen you before.”

“I live here!” Severin said, but he knew it wouldn’t make any sense to them.

After a while, Severin knew he was beginning to become like the Pettibones. He was fading from his own world and being absorbed into the world of 1937, the world of the Pettibones. When he ate with them now, the food seemed real to him. He put it in his mouth, chewed and swallowed, and it made him feel full. And when they spoke, he could hear their voices more clearly now without the underwater sensation.

“We love having you here,” Marcella said to him. “You don’t have to go back to that other place if you don’t want to. We have plenty of room for you here.”

“Yes, I think I’d like that,” Severin said.

“I always wanted a brother about my own age,” Gunner said. “I’ll show you my stamp collection and we can have a lot of fun together.”

“I’ll teach you to do the waltz,” Phoebe said, “and you can help me with my arithmetic homework.”

“I wasn’t planning on having another son,” Clyde said with a laugh, “but those things happen!”

Severin had much to tell them about his own time, which to the Pettibones was the future, but the more time he spent with them the more he became like them and forgot about his own time. He took the name Severin Pettibone and after a while he forgot he had ever been anything else. Clyde was his father, Marcella his mother, Gunner his brother and Phoebe his sister.

As for the fat-lady invalid upstairs in the master bedroom, it took her a while to realize that the old Severin Dinwiddie was gone and wasn’t coming back. She cried and wailed and called the police and insisted they find her little boy, but secretly she was glad he was gone.

Copyright © 2024 by Allen Kopp