Beautiful in the Way of Mannequins

~ A Short Story by Allen Kopp ~

Poppa’s face was dry and lined, like old leather. The red pouches under his eyes made his eyes look half-closed, even when they were open all the way. His mouth was a thin, lipless line in which a Marlboro cigarette was inserted. For sixty of his seventy years, he had smoked Marlboros, an untold and uncalculated number of them.

He reclined in his chair that had molded itself to the shape of his body—or his body had molded itself to the shape of the chair. The room was dark and low, the perpetual cloud of smoke hanging like a pall between Poppa and the ceiling. A small lamp with a little cluster of red flowers painted on the lampshade, the only color in the room, sat on a table between his chair and Momma’s.

Poppa and Momma both puffed on their cigarettes. For them, puffing on a cigarette was part of the act of breathing. A breath wasn’t a breath without a puff to complement it. And while they puffed away they both kept their eyes on the screen a few feet in front of them. The screen was the eye on the world, the only eye, to which they had given their fealty. It didn’t matter what was on—a boxing match, a train wreck, news of the world, cowboys and Indians, romance, dancing, drama, music or laughter—it was all the same: they regarded everything the eye brought to them with the same fish-eyed blankness.

The door opened and Elma entered. Momma and Poppa didn’t look up but instead kept looking at the eye. Elma took off her coat and hat and stood in the middle of the room; she looked expectantly at Momma and Poppa, though the eyes through which she saw them were only slits.

“Beer, beer, beer!” Poppa said.

“Popcorn, popcorn!” Momma said. “Peanuts, Peanuts!”

Elma went into the kitchen to get the things they wanted and took them back into the living room. When she set the bottle of beer on the table next to Poppa’s arm, he didn’t look up, but his arm reached out, seemingly of its own accord, and brought the bottle to his lips. He took a long drink and smacked his lips and set the bottle back down.

Elma had mixed the peanuts and popcorn together in one bowl, the way Momma liked them. Momma grabbed the bowl and began eating hungrily, never looking away from the eye. Elma opened a new carton of Marlboros and stacked the packs on the table, five on Poppa’s side and five on Momma’s, and when these things were done she went up the winding stairs to her own people.

The room seemed crowded now with twelve of them. They sat or stood about in different poses. Elma had dressed, wigged and hatted them according to her own whims. There was the society lady with the fox fur, the businessman with a pencil-line mustache, the small boy standing beside the dresser in play togs, ready to catch a ball, the lady with one leg canted out, hands on hips. They all had beautiful, painted-on, perfectly proportioned faces, luminous eyes and pearl-like teeth.

Some had movable arms and legs so they might be posed sitting or reclining. Elma liked these best because they seemed more real. To amuse herself, she would sometimes dress a man in a lady’s dress—including a hat with a veil—or a lady in a man’s work clothes or overalls. She also tried different wigs and hats to get a different look or feel. In this way she amused herself for hours and kept from being lonely.

There was one man in particular she liked to whom she had given the name Frankie. His arms and legs moved and his head swiveled from side to side. His skin was soft and pliable and warm to the touch. Elma dressed him in silk pajamas and put him beside her in the bed and covered him up. On cold nights, with the light off, she would have almost sworn there was a living, breathing man in the bed beside her. It gave her a feeling of well-being unlike anything else.

For twelve of her thirty-nine years, Elma had worked in the office of a mannequin factory. All day long she sat at a desk and typed letters or did small errands for the two bosses. They liked her because she always did what she was told to do without complaint, worked for very little money, never missed work, and didn’t mind working an hour or two over when the work was piling up. She was the very rare woman who had little to say and didn’t believe that her opinions were of any importance. If they could have ordered a dozen more like Elma, they would have.

Anytime a mannequin couldn’t be used or was defective in any way, Elma asked if she might have it to keep for her own. Nobody at the mannequin factory ever asked her why she wanted the mannequins or what she did with them, but they were always willing to comply. These mannequins that Elma rescued from the trash heap she added to her collection. When she carried one of the mannequins home, people stopped to look at her, but nobody ever suggested that she was doing something she shouldn’t do or that she should be stopped. Poppa and Momma, of course, never noticed what she did and never went up the winding stairs to her rooms.

One day Elma noticed a man looking at her at the mannequin factory. She discovered his name was Alexander A. Alexander but he went by the name of Shakespeare. She thought at first that he was looking at her because he was new and didn’t know anybody yet, but a week later he was still looking at her, although she didn’t know any reason why he should.

She was delivering a typed report to one of the bosses when she met Shakespeare face to face in an otherwise deserted hallway. Instead of veering away from her and keeping on his side, he stepped in front of her and stopped her in her tracks. He put his hand familiarly on the underside of her wrist and smiled.

“I believe I know you,” he said.

All she could do was shake her head and step around him and walk on. When she got back to her desk, she was breathless and a little confused. No man had ever paid any attention to her before and when she looked at herself in the mirror she knew why. By the kindest and most generous assessment, she was hideously ugly. Her nose was crooked, her hair mouse-brown, her eyes small and ferret-like, her teeth misshapen and brown. She could never remember a time in her life when she had cared much about the way she looked or about the effect that she might have on other people. If Shakespeare spoke to her again, she would ignore him or register a complaint.

On a blustery day in fall when she was walking home in the near-dark, she realized Shakespeare had fallen into step beside her. She hadn’t seen where he came from; he was just there.

“Leave me alone!” she said. “You don’t have any business bothering me!”

She looked at him and when she saw the hurt in his eyes, she knew she had been more unkind than she needed to be.

At home it was always the same. Momma and Poppa never looked at her or spoke to her. They just sat puffing and looking at the eye. She brought their food, which some days was only pretzels, candy, popcorn or beer. When she fixed them a sandwich or a bowl of soup, they hardly ever ate it and she ended up throwing it out.

In the evening after she saw they only wanted to be left alone with their cigarettes and with the eye, she retreated to her rooms and to the people there with whom she felt comfort and peace. She began to ask herself: What kind of life is this I’m living and do I plan on doing these same things every day of my life until I die? The answer, if there was one, did not make itself known.

For the first time in her life, her sleep was disturbed by nightmares, and during the day at the mannequin factory she began to be nervous and tense. She took much longer to do her work than usual and any time one of the bosses sent her on an errand, she usually managed to find a private place, in the ladies’ room or elsewhere, to stand quietly and stare at the wall for a half-hour or so in a trance-like state before returning to her desk.

She didn’t see Shakespeare for several days and wondered what had happened to him. Maybe he wasn’t suited to his job, spray-painting mannequins, and had already been fired. She was more than willing to put him out of her mind.

The next time she saw Shakespeare, it was not at the mannequin factory but on the sidewalk down the street. When she saw him coming toward her in a crowd, she looked away but, again, he stopped her in her tracks and put his hand on her arm.

“I believe we knew each other once,” he said.

She stepped around him and kept going, eyes to the ground.

“Have you ever thought about trying a little makeup?” he said in a loud voice.

“Mind your own business!” she snapped.

Then one day Elma found herself on a tiny elevator with Shakespeare, going up to the fourth floor. For a couple of minutes, at least, she was stuck with him in close quarters and couldn’t walk away.

“We knew each other in school,” he said.

She looked at him with distaste. “I don’t remember,” she said.

“It was a long time ago.”

“I never saw you before,” she insisted.

On a rainy Friday as she was leaving work, Shakespeare was going out the door at the same time she was.

“Would you like to talk?” he asked.

“No!” she said.

He walked along beside her and there was nothing she could do but keep walking with her eyes down and pretend he wasn’t there. When they came to an establishment where liquor was sold, he looked at her and inclined his head to indicate they should enter. Without knowing why, she let herself be led inside.

They sat side by side at a bar. She had never been inside a barroom before and only wanted to leave. When a beer in a glass was set in front of her, she looked at it and didn’t seem to know what she was supposed to do.

“It’s a small world,” he said. “Isn’t it?”

“I don’t know why you’re bothering me,” she said, “but I want it to stop.”

“Do you think whenever a person speaks to you, they’re bothering you?”

“I want to be left alone,” she said. “I have to be getting home.”

“Wait a minute,” he said. “I have something I want to give you.”

“I don’t want it.”

He gave her a tiny pill that he took out of a little brown envelope in his pocket. She looked at the pill in her palm and started to give it back. “What is it?” she asked.

“It’s something that will make you feel better. About the world and about life. Take it and see if it doesn’t.”

“You’re a dope dealer?” she asked.

He laughed, showing his long teeth. “All things are relative,” he said.

“I don’t know what that means,” she said. “I have to be getting home.”

“Put it in your pocket and take it with you. Tomorrow is Saturday and you don’t have to go to work. Take the pill in the morning when you’re alone and see if you don’t have a wonderful day.”

“I won’t take it,” she said. “I’ll flush it down the toilet.”

He laughed again. “Suit yourself!”

When she walked into the house, she was more than usually disgusted by the sight of Momma and Poppa sitting in their chairs staring at the eye and puffing on their cigarettes. She wanted to leave again but the thought of the bleak, wet, lonely streets leading nowhere stopped her. Without acknowledging to Poppa and Momma even that she was home, she went up the winding stairs to her rooms and to the only people in the world who knew and loved her.

*****

Elma awoke, more than ever conscious that Frankie, in the bed beside her in silk pajamas, wasn’t a real person, but a mannequin with movable arms and legs. She groaned and sat up and covered Frankie with the blanket so she wouldn’t have to look at him. It was Monday morning and a squinty-eyed look at the clock revealed that it was already later than she thought.

On this morning she took more pains with her appearance than usual. She stood under a spray of scalding water and washed her hair; after it was dry, she brushed it vigorously in an attempt to give it some body. She had found an ancient tube of lipstick and this she dabbed to her lips, sparingly, to give her face a little color. When she was dressed, she tied a red-and-blue scarf around her shoulders, looking at herself in the smoky dresser mirror to determine if any of these little blandishments had made a difference.

At the mannequin factory, she didn’t say a word to anybody. She went to her desk and began doing the work that had been left to her by people she never saw and who treated her, not badly, but like a piece of the furniture.

In the middle of the morning, she was aware of somebody standing in the doorway looking at her. She turned toward the wall and blew her nose loudly into a wad of used tissue. When she turned back around, the person was still standing there, making clucking sounds with his tongue to get her attention. She looked up and when she saw it was Shakespeare, her heart gave a little lurch in spite of itself.

“Are you looking for someone?” she asked.

“Only you,” he said.

She bit her lip and said, “Humph!”

“You’re looking radiant today,” he said.

She knew how hideously ugly she was; she believed that anybody who suggested otherwise was making fun of her.

“Do you want me to tell Mr. Hilyer you’re here to see him?” she asked.

“I’m not,” Shakespeare said. “I’m here to see you.”

“How many times do I have to tell you?” she said. “I’m not interested in your little games.”

“You don’t mean that,” he said. “Your heart cries out.”

She stood up and walked to the door of Mr. Hilyer’s office and put her hand on the knob and started to open the door. It was the cue for Shakespeare to leave.

“I’ll see you later,” he said, waggling his fingers at her and disappearing around the corner.

She sat back down at her desk and Mr. Hilyer came out of his office. He was unused to hearing her speak at all, so he asked, “Who were you talking to?”

“Nobody,” she said. “Nobody here.”

At lunchtime she went down to the lunchroom to get a little carton of milk to have with her roll and apple. Shakespeare was sitting at one of the tables and when he saw her he jumped up and came toward her. She got her milk as fast as she could and turned her back to him, but he followed along behind her.

“Stay and talk for a little while,” he said. “Have a cigarette.”

“No!” she said. “Some of us have work to do!”

“Don’t you want to ask me anything?” he asked.

“Only why you’re bothering me!”

“So you want me to leave you alone, then?”

“Yes!”

“Well, why didn’t you say so?” He laughed and was gone.

When she left work at the end of the day, Shakespeare was waiting for her at the door, as if it was something he did every day.

She groaned and said, “I don’t want to see you!”

“I have a car today,” he said. “I’ll give you a ride home.”

“I don’t want it!”

Nevertheless, she let herself be led to his car, an old black Cadillac, and got in on the passenger side when he unlocked the door.

“At least it isn’t raining today,” he said as he got in and started the car. The car made a vroom-vroom sound and he said, “This is a classic. They don’t make them like this anymore.”

“You can let me out anywhere,” she said. “I’m used to walking.”

“You don’t want to have a drink with me?” he asked.

“No! I don’t drink!”

He turned and looked at her with a smile and she turned her face away.

“You don’t much like the way you look, do you?” he said.

“What business is it of yours?”

“I can help you if you’ll let me.”

“Let me out at the next corner.”

“All your life you’ve been told you’re ugly and they’ve got you believing it.”

“That’s enough. Let me out!”

“No, I don’t want to,” he said.

“Why do you persist in bothering me?” she asked. “Just look at me!”

“You know I spray paint mannequins at the mannequin factory?”

“I’m so happy for you!”

“No, you’re not. You’re very unhappy.”

“You know nothing about me.”

“I know more than you think I know.”

“If you don’t stop bothering me, I’m going to tell Mr. Hilyer.”

“What do you think he’d do? Is he your boyfriend or something?”

“You can let me out anywhere,” she said. “I’ve had enough of this and I’m going to walk the rest of the way.”

“Did you take the pill I gave you on Friday?”

“Pill?”

“Don’t you remember? In the bar after work I gave you a pill and told you to take it when you got home.”

“I remember saying I was going to flush it down the toilet.”

“Did you take it?”

“I flushed it down the toilet.”

“I wanted you to take it.”

“Why?”

“Because it will make you happy and beautiful, at least for a little while.”

“I was going to call the police and tell them you’re distributing illegal drugs, but I couldn’t remember your name and I didn’t think you were worth it, anyway.”

When he pulled up in front of her house, she realized she hadn’t told him where she lived. “How did you know?” she asked.

“I’m a good guesser.”

She opened the door and started to get out.

“Wait a minute,” he said. “I have something I want to give you.”

“I don’t want anything you have,” she said.

He took a pill out of a little bottle and put it in the palm of her hand. “Don’t flush this one down the toilet,” he said.

“What is it?”

“It wouldn’t help you to know the name.”

“You’re not going to make a dope fiend out of me, if that’s what your little game is.”

“It’s not like that,” he said.

“What will it do to me?”

“It won’t hurt you, I promise.”

“What will it do to me?”

“You’ll see the Celestial City.”

“Does that mean I die?”

“There is no death in the Celestial City.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, but the main thing is I don’t give a shit.”

“You will,” he said. “Give it time.”

For the rest of the week she didn’t see Shakespeare at the mannequin factory. She was both relieved and alarmed.

By the time the work week was over, she was sick. She had caught a cold and ached in every part of her body. When she tried to eat a little breakfast on Saturday morning, she threw up on the kitchen floor. After she cleaned up the mess, she locked herself in her room and went back to bed.

As she lay there, she remembered the pill that Shakespeare had given her. Without thinking too much about it, she arose from the bed, took it out of its hiding place in the dresser drawer, and swallowed it.

She lay back down on the bed, composing herself for death, legs straight out and hands over her abdomen. She knew she was taking a terrible chance by swallowing a pill that a person like Shakespeare had given her, but she was past caring. If she died, she would never have to see Momma and Poppa again or the mannequin factory, which had lately become more and more odious to her.

She felt nothing for a few minutes, but then the room began to move, not in a vertiginous but in a joyful, musical way. The people around her, the mannequins she had rescued from destruction at the mannequin factory, began to move around her in time to a beautiful melody. They were fluid in their motions, even the mustachioed outdoorsman and the little boy at play. She felt herself—saw herself—being lifted up from the bed, suspended in the air, surrounded by the mannequins in a circle of light and love. And just above her head, where the ceiling had been, the Celestial City opened up in a burst of brilliant light and untold beauty. A man stepped forward from the light, perhaps a mannequin and perhaps not; she wanted to go to him but was for the moment unable to move her arms and legs. Slowly the man dissolved into nothingness and she fell back on the bed in blackness and utter despair.

*****

She was without illusion. She was ugly. She would never be anything but ugly. Ugly was not without its compensations, though. People didn’t ask her for directions or to lift things down for them at the grocery story; they looked through her as if she wasn’t there. She had heard about women (mostly from watching the eye, which she didn’t bother with much, anymore) having terrible problems with boyfriends and husbands, or just men in general. And, then, of course, there were the children that resulted from the relationships with these men; the children were a whole different set of problems that one might avoid by being ugly. She didn’t choose to be ugly; it was just the way things happened. If she had been given a choice, would she have chosen to be beautiful with all its attendant problems? No, she would have chosen not to be born at all.

Shakespeare might have had any of a dozen women at the mannequin factory—and not just mannequin women, either, but real ones. He was, if not exactly good-looking, at least passable, with a good smile, abundant hair, clean fingernails and a flat stomach. Why he would pay any attention at all to Elma the Ugly was beyond her ken.

She was sitting at her desk when he came in and placed a chocolate bar with nuts in front of her. Her first instinct was to say she didn’t want it, but when she saw the way he was smiling at her she couldn’t bring herself to say it.

“What’s this for?” she asked.

“You don’t like chocolate?” he asked.

“Why me?”

“Because we’re friends.”

“No, we’re not.”

Her voice didn’t have quite the edge that it had before. She was softening toward him.

“Have lunch with me today,” he said.

“I never eat lunch.”

“I have something I want to discuss with you.”

“I don’t want to hear it.”

“Mr. Hilyer is out of town at a mannequin convention.”

“So?”

“Nobody will know if you step out for lunch today.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“I’ll come by about a quarter to twelve. We’ll go to a spaghetti place I know.”

“I don’t like spaghetti.”

“I’ll see you at a quarter to twelve.”

She spent ten minutes in the ladies’ fluffing up her hair and painting her lips with a lipstick she had taken to carrying around with her. At a quarter to twelve, her heart was pounding and she felt nauseated.

He showed up exactly on time and she was waiting for him.

The spaghetti restaurant was a ten-minute walk from the mannequin factory. He walked leisurely, as if he had all day. She worried about how much time she was going to be away from the mannequin factory but said nothing.

Over a plate of spaghetti, he leaned forward and said, “You look different now. Better.”

“There is no reason for you to make personal remarks about the way I look,” she said.

“You saw the Celestial City,” he said. “That’s why you look different.”

“I will admit that I took the stupid pill you gave me because I was feeling very bad.”

“And you were looking for an escape.”

“I thought I was going to die and I wouldn’t have cared much if I had.”

“You saw the Celestial City.”

“I saw something. I don’t know what it was. I won’t ever do it again.”

“It made you feel better, though, didn’t it?”

“I don’t know why I don’t call the police and report you for the drug dealer that you are.”

“That’s not what I am.”

“I have to get back to the mannequin factory. I shouldn’t even be here.”

“Nobody will know you’re gone.”

“Thanks for the lunch,” she said. “Let’s not do it again.”

“I have something important I want to discuss with you,” he said.

“No matter what you have to say, I don’t want to hear it.”

“I want you to meet me after work on Friday.”

“How do I know you won’t murder me?”

He surprised her by laughing. “If I wanted to murder you,” he said, “I could have already done it. Remember, I know where you live.”

“Let’s just forget the whole thing,” she said. “Forget you’ve ever seen me. Forget you know where I live.”

“It’s about your parents.”

“You don’t know anything about them. They keep to themselves and so do I.”

“I don’t want to say more now than what I’ve already said. Meet me on Friday at five o’clock.”

“I won’t,” she said.

“Yes, you will.”

He was waiting for her at the door as she exited the mannequin factory on Friday. She sighed when she saw him but went with him to his Cadillac.

He drove out of the city into the country and stopped at an old cemetery, the Cemetery of the Holy Ghost.

“Is this where you’re going to kill me?” she said.

“If I was going to kill you, this would probably be the place to do it,” he said.

They got out of the car and he led her past a myriad of grave monuments, down a hill and then up another hill to a recent grave that didn’t have a headstone. The dirt was still mounded up and there were some remnants of old flowers.

“I need to get home,” she said. “I have things to do.”

“I’ll bet you’d never guess whose grave this is,” he said.

“No, and I don’t care.”

“It’s my mother. She died almost four months ago.”

“All right. Now that we’ve seen it, can we go?”

“Not just yet. She made me promise before she died that I’d find you and tell you the truth.”

“The truth about what?”

“Let’s find someplace to sit down.”

“I’d rather stand. That way I’m closer to leaving.

“Suit yourself. Do you want to hear this or not?”

“Do I have a choice, now that you’ve dragged me out here?”

“Your father is Percy Costello and your mother is Estelle Costello? Is that right?”

“How do you know their names?”

“When my mother was young, she was a baby snatcher and she was never caught.”

“She was a what?”

“Just let me explain. She made her living as a baby snatcher. She was never married to my father and she needed money to raise me.”

“What does that have to do with me?”

“Percy and Estelle Costello are not your real parents.”

“Are you crazy? What are you talking about?”

“When you were nine months old, my mother kidnapped you from your real parents and sold you to Percy and Estelle for a thousand dollars.”

“That’s not true.”

“The police looked for you but after about three years they figured you were dead and gave up. Your real parents were dead by then, anyway, killed in a plane crash, so there was no reason to keep up the search.”

“I don’t know what your game is, but I don’t believe a word you’re saying.”

“My mother told me all about it from the time I was old enough to understand. She never stopped feeling guilty over it. She used to sit at night and cry about it. She had newspaper clippings about your disappearance as a baby and how the police never had any leads.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“Your real name is Paulette Merriman. Your father was a policeman and your mother a high school teacher. You were an only child. You lived in Lincoln, Nebraska.”

“I was never in Nebraska.”

“Percy and Estelle wanted you to help around the house because they had trouble walking and doing things for themselves. They promised my mother they would never mistreat you and would give you a good home, like a puppy or a kitten. She told them she’d keep an eye on them to make sure they kept up their end of the bargain. If there was any reason for her to think you were being neglected or mistreated, she threatened to go to the police and tell them the whole story.”

“I think you have me confused with somebody else. I never knew anybody named Paulette Merriman. That’s not my name.”

“When I was in high school, we lived about three blocks from you and we both went to the same school. I used to see you at school every day. You were so shy you wouldn’t even look at me.”

“I don’t remember.”

“My mother used to park on the street and watch you go in and out of your house. She would ask me almost every day if I saw you at school. She would want to know what you were wearing and if you seemed clean and happy.”

“What did you tell her?”

“That you were like a little mouse afraid of being eaten by the cat.”

“I don’t believe any of this.”

“There was an English teacher with a fake nose. Her name was Miss Jilson. I’ll bet you remember her, don’t you?”

“That doesn’t mean you went to the same school.”

“A boy a grade ahead of us got drunk and passed out on the highway at midnight and was hit by a car and killed. Everybody talked about it for weeks.”

“Ellis Persons,” she said. “That was his name.”

“Now do you think I’m lying?”

“Just because you know about Ellis Persons isn’t proof that what you’re saying is true.”

“Just think about what I’ve told you. I think it’ll all start to make sense after a while.”

“You’re a liar. Take me home now.”

“Ask Percy and Estelle if they’re your real parents. Ask to see your birth certificate. Ask them where you were born and when.”

“They’d only pretend they don’t know what I’m talking about. I’d never get the truth out of them.”

“Didn’t you always having the feeling there was something missing in the way Percy and Estelle behaved toward you? They didn’t mistreat you, but not mistreating you was the only good thing you could say about them.”

“How do you know so much about it? I want to go home now.”

On the way back to town, despite her objections, he stopped at a road house. They went inside and sat at a back booth, had chili and ribs. The place was quiet. She had her first beer out of a bottle and then a second.

She didn’t say anything for a long time and then she said, “All these years I’ve cleaned up after them, taken them their snacks, breathed their cigarette smoke, helped them to bed and to the toilet, and I’m not even related to them.”

“So, do you believe me now?”

“If it’s true—and I’m going to have to see some proof—I’m going to kill them.”

“No, you’re not. You’d go to prison.”

“Not if I do it right.”

“I have eighteen thousand dollars. That’s enough for you to go far away and live decently until you can find a job.”

“I don’t want money from you.”

“It’s not from me. It’s from the person who kidnapped you and ruined your life. I told her I’d see that you got it. She thought it would square her in heaven.”

He didn’t take her home until eleven o’clock, and when he pulled up in front of her house he shut off the engine.

“I want you to see my people,” Elma said.

“Percy and Estelle?”

“No. I mean my real people upstairs in my room.”

Momma and Poppa were sitting in front of the eye, puffing away in a fog of cigarette smoke. When Elma came into the house with a person they didn’t know and had never seen before, they didn’t even look up.

“Get me some cheese crackers!” Momma said.

“About out of smokes here!” Poppa said.

“Good evening, sir!” Shakespeare said. “How are you, ma’am?”

“They don’t hear you,” Elma said. “They’re in a trance. That’s what the eye does to them. And the Marlboros.”

“This is no way for a person to live,” Shakespeare said.

After Elma got Momma and Poppa the things they wanted, she took Shakespeare up the winding stairs to the rooms above and, once they were inside, she locked the door.

Shakespeare’s enthusiasm for the mannequins was equal to Elma’s own. He admired all the figures in her collection, their clothes and especially the way their faces made you feel that everything was going to be all right.

“I paint their faces, you know,” he said. “They speak to me in my dreams.”

Frankie, in the bed in the silk pajamas, was her favorite, she said. She pulled back the covers and picked Frankie up and set him on his feet beside the bed.

“I have another pair,” she said. “I want you to put them on and take Frankie’s place tonight.”

She took a pair of yellow-and-red silk pajamas out of the dresser drawer and handed them to Shakespeare. As he undressed, she turned away and prepared herself for bed.

So now she lay in bed, with Shakespeare beside her in Frankie’s favorite silk pajamas. She turned off the light and lay back and pulled the covers up to her chin. She didn’t need the Celestial City or anything else as long as he was there beside her, living and breathing.

*****

Shakespeare was gone in the morning and in his place in the bed was Frankie the mannequin. Elma couldn’t remember at first what had happened the night before, but when she saw the yellow-and-red silk pajamas folded neatly on the chair, it all came back to her.

She and the man from the mannequin factory she had been trying to repel, the man who angered her and made her forget what she was doing, the man known as Shakespeare, had spent the night sleeping side by side in the bed. Only sleeping, it must be emphasized—neither of them had crossed the invisible line that ran down the middle of the bed.

She gave Momma and Poppa their breakfast of sugar corn pops and donuts and, after they were finished eating and installed in front of the eye, she set out to the market to buy beer nuts and Marlboros. It was a cold, blustery day and she wore her coat made of genuine artificial monkey fur, the only one of its kind in the world, and the white fur hat with her hair tucked up inside. People looked at her curiously but she ignored them, even though she thought them rude.

She bought three cartons of Marlboros instead of two and, as she stood in line to pay for them, she thought of the many, many Marlboros she had bought in her life. Sometimes it seemed all she had ever done in her life was buy Marlboros. Momma and Poppa should rightly be dead by now, considering how many Marlboros they smoked and how much unhealthy food they ate, but the years went by and still they sat in their chairs, smoking, eating snacks and staring at the eye.

As she walked home, she told herself that the three cartons of Marlboros would be the last she would ever buy because she was going to kill Momma and Poppa. She didn’t know yet how she would do the deed; it was going to take some careful planning.

A door that had always been closed was now open. She had no blood connection to Momma and Poppa. They had bought her for a thousand dollars when she was a baby. Not only had they used her all her life as an unpaid servant, but they had lied to her. She would have gone on in the same way through all the weary years to come, but not now, though—now that she knew the truth.

After high school, she had no friends and no life other than keeping house for Momma and Poppa and taking care of them. She rarely left the house except to buy food and other things they needed. Poppa had an old car that he kept locked up in the garage out back, but when Elma told him she wanted to learn to drive, he refused, saying that the car was too valuable to entrust to somebody like her. And, besides, she had two legs, didn’t she? That’s all she, or any other woman, would ever need.

When Elma was twenty, Momma had a serious operation and almost died. She was in the hospital for weeks. When she went home, she had a trained nurse to help her to recover, but she dismissed the nurse after two days and insisted that Elma do the nurse’s job. Through many long days and nights, Elma stayed by her bedside, while Poppa sat in his chair smoking Marlboros, watching westerns, news broadcasts, and war movies on the eye.

Elma always thought she would get a job the way other people do, but Momma and Poppa wouldn’t let her. They said she had too much work to do at home. She would have to prove to them she could handle the pressures of a job and all her work at home besides before they would even consider letting her get a job. They wanted her to get a full night’s sleep every night so she would be able to do all the things they needed her to do during the day. No, working at a job outside the home was out of the question.

In high school she took typing and shorthand and was good at them. She bought an old typewriter from the school for twenty dollars and this she used to keep up with her typing. She didn’t want to be completely useless in the world. Instinct told her that Momma and Poppa would die, or maybe turn her out after they got tired of her, and that she would have to earn her own living.

Poppa had some financial reverses when Elma was in her mid-twenties and it turned out that he and Momma didn’t have nearly as much money as they thought they had. There wasn’t going to be enough money to keep up with monthly expenses, so Elma went to work at the mannequin factory.

The job didn’t pay much, but Elma had never worked before so it seemed a princely sum. And, if she was frightened out her wits to be out in the world for the first time, she quickly adapted. In spite of her odd appearance and her eccentricity, she was good at her job because she ignored all the distractions that other people had. She didn’t care about her appearance, never socialized with the other employees and never, ever took smoke breaks or coffee breaks.

She had been at the mannequin factory now for twelve years. Her youth was gone and where did it go? Her beauty? She never had any to begin with. She was what they call a spinster. She had never been out on a date with a boy or a man and, when she looked at herself in the mirror, she knew why.

She had gone through a period in school where boys made fun of her, made pig sounds or monkey sounds when she walked into a room, but after they grew tired of her and desisted, they ignored her entirely, which, in a way, was worse than being laughed at. No male of the species had ever paid her any attention at all until Shakespeare came to work at the mannequin factory.

She still didn’t know quite what to make of Shakespeare. Now that she had had a day and a night to think about all he told her at his mother’s grave, the whole thing made perfect sense—all the pieces fell into place. Momma and Poppa never had any real regard for her because they had purchased her the way they would purchase a refrigerator. To them she was nothing more than a commodity. How could she have not seen it before? Did she not know enough about the world by the time she was grown to know how parents are supposed to behave with a daughter?

Sunday evening there was a knock at the door. Elma never answered the door, but she somehow knew it was going to be Shakespeare and it was.

“Can I come in?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “I’d rather you didn’t.”

“You’re getting better,” he said. “A while back you would have told me to leave you alone and then slammed the door in my face.”

She attempted a small smile but it turned into a grimace. “I was just about to roll up my hair,” she said.

“Come out for a while,” he said.

“Another cemetery?”

“No, just…out and back.”

She put on her coat and hat and left without a word. Momma and Poppa wouldn’t even know she was gone. They had all the smokes and all the snacks they would need for the evening.

“Have you thought about what I told you on Friday?” he asked after he had driven a couple of miles through town, out past the high school, the shoe factory and the sewage treatment plant.

“Yeah, I’ve thought about it,” she said.

“Do you believe me?” he asked.

“Yes, I believe you. Why would you say such a thing if it wasn’t true?”

“Nobody ever offered to give me eighteen thousand dollars to go away and start a new life,” he said.

“I told you I’m not going to take any money from you,” she said.

“It’s not from me. It’s from my mother. I thought I already made that clear.”

“It doesn’t matter. I’m going to stay right here and kill Momma and Poppa after what they did to me.”

“Do you want to go to prison?”

“It’d be worth it to see them dead,” she said.

“Don’t you think it would be better if you quit your job at the mannequin factory and went far away and didn’t tell Momma and Poppa where you were going? Wouldn’t that be punishment enough? Then they’d have to do things for themselves, get their own beer and cigarettes, instead of having somebody to wait on them.”

“No, I know them. They’d find themselves another small child to buy, the way they bought me. Probably an older one that would be beneficial to them right away. Six or seven years old. Old enough to fetch and carry and make beds and clean floors. I’m not going to let them do that.”

“Go to the police, then, and tell them the whole story.”

“I don’t have any proof. They’d think I was just some neurotic bitch with an axe to grind against my parents.”

“Killing them is not the answer, though.”

“Haven’t you ever heard of a revenge killing?”

“Only in the movies.”

He drove twelve miles to the next town and into the shopping district. The stores were closed and the streets nearly deserted, but he parked the Cadillac on the street and got out. She followed him, afraid to sit in the car alone.

He walked into the middle of the next block, to Pasquale’s Department Store, purveyors of high fashion. People with money shopped at Pasquale’s.

“What are we doing here?” she asked. “The store is closed. It’s Sunday night.”

“I want to show you something.”

In a broad display window were four female mannequins, spaced evenly apart: one blonde, one brunette, one auburn-haired and one with hair the same color as Elma’s fur hat.

“This one’s Rochelle and that one is Vivian,” he said. “The next one is Ruby and on the end is Charlotte.”

They were all beautiful, of course, dressed in evening gowns and swathed in jewels and furs. They were the society ladies that factory workers don’t ordinarily see.

“You drove all the way over here to see them?” Elma asked.

“We made them at the mannequin factory. I painted the faces. Aren’t they lifelike?”

“You can almost see them breathe.”

“Which one do you like best? Which one would you most like to look like?”

She chose auburn-haired Vivian in the gold gown, and he said, “I thought you’d choose her.”

“Does she have a last name?”

“Vincent. Vivian Vincent.”

“At least it’s not a grave you’re showing me this time.”

“I can make you as beautiful as Vivian Vincent.”

He took hold of her arms from behind and moved her to the side so that her face was reflected in the glass over Vivian Vincent’s face. “See? Elma becomes Vivian Vincent.”

“She’s a mannequin,” Elma said. “I’m not. What are you going to do? Paint my face the way you would a mannequin’s? And what about the clothes? All my clothes are ugly, just like me.”

He laughed. “It doesn’t hurt to imagine, does it? You play imaginary games with your mannequins all the time in your room, don’t you? You imagine that Frankie in your bed in the silk pajamas is a real man and that the other mannequins talk to each other and talk to you. It makes you feel good. Less alone in the world. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

“This morning when I woke up, I thought Frankie was you, or you were Frankie. You and Frankie are the same. I think I’m insane and always have been.”

“No more insane than anybody else,” he said. “You have to be at least a little insane to live in this world.”

On the way back, he said, “You don’t have to kill Momma and Poppa. I’ll take care of them for you.”

“You’ll kill them?”

“No, better than that.”

When he pulled up in front of Elma’s house, he turned off the ignition and, without a word, the two of them went inside. Poppa and Momma were immersed in their Sunday evening programs and didn’t even look up.

“Good evening, sir!” Shakespeare said. “Good evening, ma’am!”

“They don’t hear you,” Elma said.

As before, she took him up the winding stairs to her rooms and, once they were inside, she locked the door. They listened to the wind outside for a while and then Shakespeare gently removed Frankie from the bed and set him on his feet, as before. He slipped out of his clothes and into the red-and-yellow silk pajamas and he and Elma got into bed, both observing the invisible line down the middle.

“Do you want to see the Celestial City?” he whispered.

He took two pills out of the pocket and gave one to Elma and took the other one himself. In two minutes, the room began to shimmer and whirl and the mannequins began to dance with each other around the bed. The ceiling receded and in its place was the Celestial City, filled with unearthly light and happiness. Elma saw herself and she was as lovely as Vivian Vincent, even more so, and Shakespeare was handsome beyond believing—every bit as handsome as Frankie in the silk pajamas but better because he was alive.

The Celestial City was not a place for human language, but Shakespeare somehow conveyed to Elma this message: When you wake up you’ll find Momma and Poppa greatly changed.

Elma didn’t know how long she was in the Celestial City—it was time without measure. When she woke up, she wasn’t surprised to find that Frankie the mannequin, instead of Shakespeare, was in the bed beside her. Her first thought, though, besides Frankie and Shakespeare, was how, and in what way, Momma and Poppa were “greatly changed.” She put on her bathrobe and slippers and went down the winding stairs.

Momma and Poppa were in their chairs, as usual. Momma held a cigarette on the way to her mouth and Poppa held one between his lips, although both cigarettes had gone out. Across the room, the eye was blatting at them in its usual way, but Momma and Poppa weren’t seeing it because their eyes were made of unseeing glass. If Elma had taken a knife and cut them open, she would have found only stuffing inside.

Though they were now mannequins, they weren’t beautiful in the way of mannequins, but as ugly as they had been in life. Every wrinkle on their faces, every pouch and every crease was there; their eyes were small and rodent-like and their mouths hard and mean. Momma’s hair was iron-gray and unkempt and Poppa’s shirtfront held dribbles of all the food he had eaten in the last week. Elma gave them one long and satisfying stare and went back up the winding stairs.

Frankie had risen from the bed and was sitting in the chair, his face radiant with warmth and good will. His flexible arm was extended and in his flexible hand was an envelope with Elma’s name written on it. When she opened it, she found eighteen thousand dollars in cash.

She bought, for the first time in her life, some fashionable clothes that looked good on her and that complemented her luxurious auburn hair. She bought a large suitcase and packed all her new things in it and left the old things out.

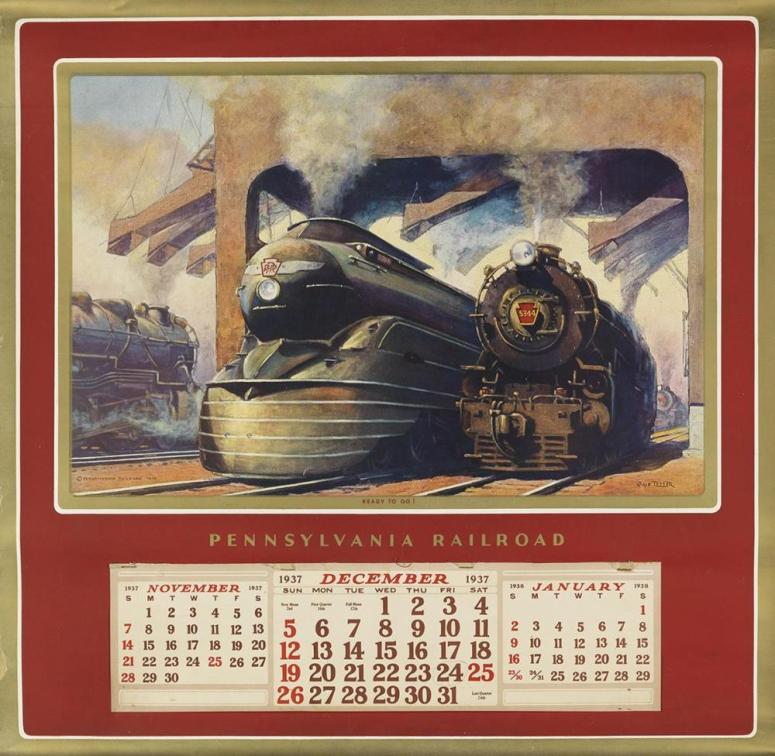

She said goodbye to the mannequins in her room and left the house for the last time. She took a taxi to the train station and there bought a ticket to Lincoln, Nebraska, traveling under the name of Paulette Merriman.

She would spend a few days in Lincoln and see if there was any of her real family left who might remember what had happened to her when she was a baby. After that, she would keep going as far west on the North American continent as she could until the tracks ran out.

Copyright 2024 by Allen Kopp