At the Time of His Disappearance

~ A Short Story by Allen Kopp ~

Trent arrived home from school at the usual time. He threw down his school books and went into the kitchen. His mother was sitting at the kitchen table, reading a magazine and smoking a cigarette. Without a word of greeting, he ate some cookies and drank a glass of water, standing between the table and the back door. When he was finished, he set the glass on the table and went out the door.

“Dinner in an hour!” she called, but he gave no indication of having heard her.

It was October and the yard was full of golden sunlight and the smell of leaves. The yard was a refuge for squirrels and birds and other small animals. It was, by far, the best place to be on an autumn afternoon. And it was private. Nobody ever came snooping around. The nearest neighbor was over a mile away. The boy had it all to himself.

Abutting the yard at the south side was an old cemetery. The boy spent a lot of time in the cemetery. He loved the old gravestones and the elaborate growth of trees, bushes, vines and weeds. It was a private world unto itself. The newest grave that he had found so far was fifty years old. If there were any graves more recent than that, he had yet to find them. It was a lost world with all those long-ago dead people. He imagined some of them in their graves, exactly as they were when they were when they were alive. He could hear them laughing and whispering. Sometimes they reached out and touched him on the shoulder or the back.

From the bay window in the dining room, his mother watched him go into the cemetery. She told him to stay out of there, but since he turned twelve he had a mind of his own and he did exactly as he pleased. That was the problem with children getting older, she thought.

She believed he was developing a morbid interest in the dead because of all the time he spent in the cemetery. Any time she didn’t know where he was, it only took one guess to figure it out. One night she heard him talking long after he should have been asleep, and when she opened his door and asked him who he was talking to, he said he was talking to a sixteen-year-old boy who died in a flood in 1893.

It was time for the evening meal, and still the boy hadn’t come back. She was going to have to have a very serious talk with him. He might at least show some respect for her after all the trouble she went to to cook the dinner.

She put on a sweater and went out the back door to try to find him. She went all the way around the house, calling his name, but she knew he wasn’t there; he was in the cemetery.

She went to the entrance to the cemetery and stopped. She called his name, but she knew he wouldn’t answer, even if he could hear her. He loved playing tricks on her. It would be just like him to jump out at her from behind a gravestone and make her jump and scream. And of course he’d laugh at her and call her a panty waist.

It was almost dark now. She went back to the house and sat down at the table and began eating the food she had fixed. She could only manage a few bites. She was nearly in tears. She was a little worried about him, but she assured herself he was all right and had just lost track of time, as children do.

By ten o’clock, his customary bedtime, he still hadn’t returned. She got her flashlight out of the drawer and went outside. She walked all the way around the house, calling his name, shining the light into the darkest places. She didn’t see any sign of him. She knew the cemetery was the place to look.

She had been in cemeteries before, but never at night and never alone. She assured herself that the cemetery was full of people long dead. There were no ghosts, nothing to bother her or cause her worry. She had to find her son, and she couldn’t be a big baby about it. Maybe he was in trouble. He might have fallen and broken his leg or something.

She gathered her courage and, walking slowly, shone her light all around, at the tops of the trees and all over the ground. Some of the gravestones were huge slabs, and others were so small you might easily trip over them if you weren’t paying attention. She called his name every few feet, but her voice was drowned out by the wind and the rustling leaves.

There was nothing out of the ordinary in the cemetery. Just the graves of those long forgotten. There were no signs of the boy having been there. All she could think to do was go back to the house and wait for him to return.

Rather than go to sleep in her bedroom upstairs, she took a comforter out of a closet and made a bed for herself on the couch in the living room. If he came in the back door, left unlocked for him, she would hear him. He would come back, she believed, with a wild story about having been abducted by a spaceship. He had quite an imagination. She would be torn between laughing at him and wanting to slap his face for scaring her so.

She spent a nearly sleepless night. Any time she almost went to sleep, she would be awakened by what she thought was the back door opening and closing, or by his calling out to her across a vast distance.

At seven in the morning she called the police and told them her twelve-year-old son never came home yesterday. Within a few minutes, two uniformed officers appeared at her door. One of them was old and the other one young.

Sobbing intermittently, she told them what happened: Her twelve-year-old son disappeared in the yard and/or cemetery the day before and didn’t come home all night. She went looking for him with a flashlight and even called his name repeatedly, but it was all to no avail.

The older officer said, “In about fifty percent of these cases, the adolescent runs off on his own and comes back on his own when he gets hungry enough. Do you think he might be one of these?”

“Oh, no! I don’t think so.”

“Has he ever run off before?”

“He hasn’t run off now.”

“Might he have been abducted by strangers?”

“I don’t have any reason to think that.”

“Was he having trouble at school?

“No!”

“Was he being bullied?”

“No, I don’t think so. No.”

“Did he ever use drugs or alcohol?”

“Of course not! He’s twelve years old!”

“What about the boy’s father?”

“My husband and I are divorced.”

“Was the boy upset when you got your divorce?”

“No. He was four years old at the time.”

“Do you ever see or hear from your ex-husband?”

“No.”

“Might your ex-husband have had anything to do with the boy’s disappearance?”

“Certainly not!”

The older officer had been writing her responses on a yellow legal pad. He stopped writing and, with his pencil poised above the paper, turned and looked at the younger officer. “Can you think of anything else?” he asked.

“Was the boy, um, I mean, is the boy sexually active?” the younger officer asked.

“Of course not! He’s a child!”

“Do you have a recent picture of him?”

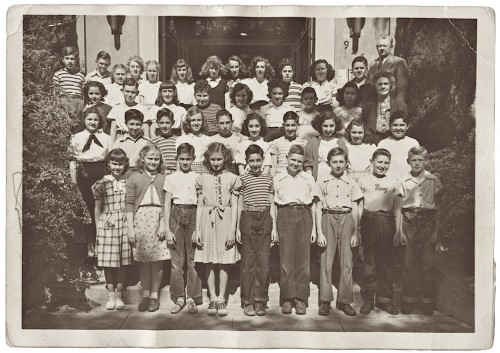

She stood up, walked a few feet, opened the drawer of a desk, took out a picture and handed it over to the older officer.

“We’ll need to keep this picture.”

“Of course.”

“What was he wearing at the time of his disappearance?”

“A shirt and pants. A jacket. A cap.”

“Does he have any distinguishing features?”

“A small mole on his right cheek.”

“Height?”

“What?”

“How tall is the boy?”

“I couldn’t say for sure. He’s rather small for his age. I’d say about four feet, six inches.”

“Can you tell us anything else about him?”

“He loves to spend time in the cemetery.”

The older officer shifted his big legs and coughed. “And why is that?”

“We have an old cemetery adjoining our property. My son has been fascinated by it for years.”

“Why is that?”

“I’m not sure. I always told him he should stay out of there.”

“And what did he say when you told him to stay out?”

“He said he felt close to some of the dead people. Don’t ask me why. He’s a lot like his father, I suppose.”

“Would you say he is obsessed with death?”

“No, I wouldn’t say he’s obsessed with death. He’s going through a phase.”

They’d keep a close watch out for him, the officer assured her. They’d send the boy’s picture and his description to every law enforcement agency in the state. They’d talk to every person in a ten-mile radius. If anybody saw anything, they’d say so.

“We’ll find him,” the older officer said.

She wanted to believe the boy would be found, but something about the way he disappeared defied logical explanation. It was going to take somebody smarter than the local police to figure it out.

They sent a team of men and boys to search the cemetery, the woods and the fields. After five days of finding nothing, they called off the search. The search would resume at a later date.

The story appeared in newspapers and on television. There was an outpouring of interest and sympathy. The mother’s phone rang all the time. Most of the calls were from well-meaning people, but a few of them were crank calls. One person claimed to know where the boy was and would divulge his location for five thousand dollars.

After the boy had been missing for a week, the mother received a phone call from a woman named Hortense Rathbone. She said she was a psychic who had been helping locate missing children for sixty years. She would do a “reading” for a hundred and fifteen dollars.

“I don’t believe in that sort of thing,” the mother said.

“I can tell things about the boy just by looking at his picture.”

“What things?”

“You’re not his real mother. You adopted him.”

“Nobody knows that. Not even he knows that.”

“Also, he’s a very old soul.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means his soul is prized.”

“Prized by whom? What are you talking about?”

“I can come to your house and do a reading. You have nothing to lose. I won’t charge you a penny if you get no results.”

“What results? Do you mean you can find him?”

“I don’t know, but I can try. No charge. This is an interesting case.”

“All right. This is Thursday. You can come on Saturday morning. And if you’re another crackpot, I’ll throw you out and I won’t be nice about it.”

“I’ve been called a lot of things,” Hortense Rathbone said.

She was a very old woman, dressed in a man’s suit and wearing combat boots. She drove a fifty-year-old Cadillac, once white but now many other colors. When she walked into the house, she wanted to walk from room to room, but she especially wanted to spend time in the boy’s room, absorbing his “essence,” as she said. She wanted a shirt of his that he had recently worn. She wadded up the shirt into a ball and held it over her mouth. She lay down on the bed where he slept and closed her eyes.

“I’ll leave you alone,” the mother said. “Come back downstairs when you’re finished.”

The psychic wanted to know every detail about the boy’s disappearance: time of day, what he said before he left the house, what he was wearing. Did he mention any other person by name? What was his mental state at the time of his disappearance? When the mother told the old woman about the cemetery, she said she needed to see it right away. It might contain an important clue that nobody else was able to see.

She spent four hours crisscrossing the cemetery, and when she came out she looked happy.

“I’ve had a breakthrough in the case,” she said. “I know what happened to the boy.”

“You know where he is?” the mother said.

“I don’t know where he is, but I know what happened to him.”

“What are you talking about?”

“There’s lots of psychic activity in that old cemetery.”

“Yeah? What about my son?”

“You said he spent a lot of time there?”

“Yes.”

“He’s passed through a portal. I can hear his voice. He’s calling for you to help him. He wants out.”

“What are you talking about? What portal?”

“It’s not something in the ground, but in the air. Think of it as being a door into another dimension.”

“Another dimension? That sounds too fantastic!”

“Well, believe it or not, portals are everywhere. People, especially children, will fall into them. It doesn’t happen very often, but it does happen.”

“But how do we get him back here?”

“I wish I knew, honey.”

The mother half-believed, half-disbelieved, the old woman’s version of what happened to her son. It made sense in a way, but it strained credulity. Another dimension? Is such a thing possible?

She began going to the cemetery every day. She wanted to find the portal that her son had fallen into. She wanted to hear his voice, pleading with her to get him out. If she just heard his voice, she’d do anything in the world to get him back home. She didn’t know how to look for a portal, but if it was there she’d find it. Being in the cemetery made her feel close to him. She’d sit for hours, listening to the wind and hoping to hear his voice.

The police investigation was going nowhere. An officer called her occasionally to report nothing at all, but also to reassure her the case would remain open.

Sometimes she caught a fleeting glance of the boy out the window, turning a corner of the house. Other times, she heard him moving around in his room late it night. He was there. She was sure of it.

Copyright © 2024 by Allen Kopp