Time That is No Time ~ A Short Story by Allen Kopp

Leatrice awoke and found herself in a strange place. It wasn’t morning and she wasn’t in her familiar room, in the bed where she had slept for the twelve years of her life. All around her was darkness, allowing her to see only a short distance in front of her; she was afraid of what the darkness might be concealing. “Hello! “Hello!” she called out for someone to help her but no one answered.

Finally someone approached her, an old woman. Leatrice had never seen the old woman before but she was somehow familiar.

“Where am I?” she asked. “Who are you? I want my mother!”

The old woman made a shushing motion with her hands. “Not so loud, child! You’ll wake the others.”

“What others?”

She noticed then that the old woman carried a glow inside her chest that allowed one to see inside her to her ribs and veins. The glow made the room a little brighter by about one candle’s worth. “What is that?” Leatrice asked in alarm. “Why are you glowing?”

“You’re glowing too,” the old woman said.

When she looked down she saw it was so. “All right, what is this? Am I dreaming?”

“In a way you are.”

“In what way? Am I asleep?”

“Asleep, yes, but not in the way you’re used to.”

“Can you please tell me where I am?”

“First things first. Tell me your full name.”

“Leatrice Geneva Fitch.”

“And in what year were you born?”

“Nineteen hundred.”

“What year is it now?”

“Nineteen-twelve.”

“That makes you twelve years old.”

“Yes.”

“You will always be twelve years old now. The year, for you, will always be nineteen-twelve.”

“What are you talking about?”

“My dear, haven’t you figured it out yet?”

“Figured what out?”

“You’ve made the transition that we all must make.”

“What transition? What is this place?”

“You have passed from one realm of existence to another, from the physical to the spiritual realm.”

“Are you saying I’m dead?”

“My dear, that word doesn’t mean anything here.”

“Well, am I?”

“If that’s the way you way you want to put it, then, yes, you are. Dead.”

Leatrice let out a breath, mostly to reassure herself that she could still breathe and said, matter-0f-factly, “I don’t like this place. I want to go home.”

“This is your home now.”

“What happened, anyway?” she asked, fighting back tears. “I don’t remember being sick.”

“You weren’t sick. It was very sudden. You got in the way of the streetcar downtown. The conductor rang his bell, but for some reason you didn’t get out of the way.”

“Funny thing, I don’t remember.”

“No, we never do.”

“And who are you, if I may be so bold? You look something like my mother.”

“I’m your mother’s grandmother, your great-grandmother. I’ve been here since long before you were born.”

“Here? Where?”

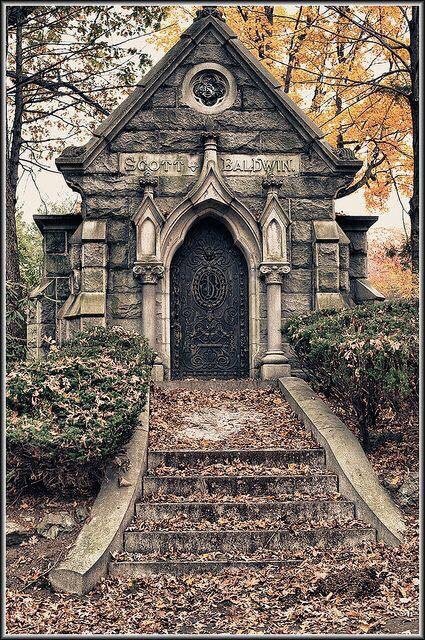

“The family crypt.”

“What?”

“Yes, you’re in the family crypt, in the cemetery, surrounded by all those who went before.”

“Oh, no! That can’t it be!”

“Why can’t it be?”

“I’ve seen the family crypt and I don’t like it.”

“You’ve only seen it from the outside.”

“Yes, and it’s scary. It seems to me that, once you’re on the inside, you’ll never get out again.”

“Well, now you’re on the inside so you’ll know firsthand, won’t you?”

Leatrice let loose with the tears she had been trying to restrain. “I don’t like this place and I want to go home! Where are my mother and father? I want to see them.”

“Where do you think they are? They’re still alive. They’re where they’ve always been.”

“Will I ever see them again?”

“More than likely you will, but who can say for sure?”

“But I have cats. What will happen to my cats now that I’m no longer at home to take care of them?”

“Your brother will take care of them. They’re his cats now.”

“Will they come here to me when they die?”

“You’ll find out in time,” great-grandmother said.

There was a lapse then, a darkness, as of a veil being drawn. When this nothingness ended (and who knows how long it might have lasted because in this place there is no time?) great-grandmother was leading Leatrice by the hand, inviting her to meet the “others.”

Cousins Parry and Lomax, twins, were ten at the time they came to the family crypt. (They went over a waterfall in a rowboat and drowned on a summer’s day.) They looked at Leatrice with curiosity. She knew from their manner that they were shy of her and didn’t know what to say.

Great-grandfather was tall and broad, wearing a dress suit, with the elaborate mustache and side whiskers fashionable at the time of his passing. (He was the one who built the family crypt so he could have his family all together in one place.) He smiled at Leatrice and patted her on the head and then he was gone.

Uncle Evan, great-grandfather’s son, was handsome in his military uniform. He entered the spirit realm in Cuba when a bullet struck him in the neck during the Spanish-American War. He smiled at Leatrice and winked and touched her on the shoulder.

Aunt Ursula was a tall, thin woman with a sad face. She carried her three-month old son, George, in her arms. George entered the spirit world over thirty years before aunt Ursula. Since Aunt Ursula arrived, she had held baby George in her arms and refused to part with him. They would be together forever and forever.

And then there was aunt Zel, great-grandfather’s sister. She was a formidable woman, coiffed and bejeweled. By her side always was her husband, Little Otis. (People called him Little Otis to distinguish him from his father, Big Otis.) He was eight inches shorter than aunt Zel, with one arm missing. (He lost his arm not on the field of battle but from the bite of a skunk.)

Uncle Jordan was dressed in an expensive dress suit, with diamond stickpin and silk cravat. He kissed Leatrice on each cheek and then he was gone. He avoided being around the other family members for very long because they were contemptuous of him. In life, he had enjoyed himself a little too much, spent more money than he had a right to spend and died, deeply in debt, in young middle age of alcoholism.

Cousin Phillip’s appendix burst when he was only thirty-two. Immediately after he entered the spirit world, his young wife married a man she hardly knew named Milt Clausen. Odette was not in the family crypt and never would be. Cousin Phillip had renounced all women, bitter than his lovely young Odette had not honored his memory by staying a widow.

Cousin Gilbert was sixteen when he entered the spirit world as the result of a crushed larynx that he sustained in an impromptu game of keep-it-away with some of his friends. Leatrice immediately saw cousin Gilbert as a kindred spirit. The glow in his chest was a little brighter than anybody else’s. When he touched her hand, she felt a kind of connection with him that she hadn’t felt with any of the others.

“How do you like being a ghost?” he asked her.

She shook her head and looked down, again on the point of tears.

“I was the same way when I first came here,” he said. “I couldn’t believe that God would have me die so young. We learn not to ask why we’re here but just to accept it.”

She nodded her head to show him she understood and he leaned in to her and whispered in her ear, “I can show you around if you’d like.”

There were other introductions but the truth was that Leatrice wasn’t paying much attention after cousin Gilbert. He gave her a glimmer of hope, somehow; not that she could go home but that she might find death and the family crypt more to her liking.

The dark nothingness came upon her then and she and all the others slept peaceably for a piece of time in the place where time no longer existed but peace was in ample supply.

When next she saw cousin Gilbert, she was delighted to learn that she might leave the family crypt at will. He showed her how to press herself against the outer wall. Since the wall was solid and she was not, she could pass through it with the right amount of concentration, a trick of the will.

The cemetery was much larger than Leatrice imagined. Gilbert took her to visit some of his spirit friends: a twenty-seven-year-old policeman in uniform; a Civil War soldier who had exchanged words with Abraham Lincoln; a victim of the Johnstown Flood (“the water came roaring down the mountain and swept away everything in its path”); a governor of the state who one day hoped to be president but never was; a group of twenty girls who died in an orphanage fire (all buried in the same grave); a twelve-year-old boy named Jesse who stood just outside his vault until another spirit came along and engaged him in conversation.

“He’s lonely and seeks companionship,” Gilbert explained.

On one of their forays outside the crypt, they came upon a funeral on a hillside that resembled an aggregation of crows because all the attendees were dressed in black.

“This is the fun part,” Gilbert said.

He walked among the mourners, pretending to kiss or touch or put his arm around certain of them. He also demonstrated the technique of coming up quickly behind them and making the more sensitive of them turn around to see who—or what—was there.

“They sense I’m there but when they turn around they’re not so sure.”

He made her laugh when he floated over a couple of old ladies in large feathered hats and, assuming a reclining position over them, pretended to pat them on the sides of their heads.

“I, for one, love being a ghost!” he said.

“Can I fly, too?” Leatrice asked.

“We don’t really fly like a duck going south for the winter. What we do is float. We float because we’re lighter than air.”

“Can I try it?” Leatrice asked.

“If you want to do it, you can.”

He demonstrated his floating technique and they spent the afternoon floating all over the cemetery.

“Maybe there are some good things about being a spirit,” Leatrice said.

“Of course there are!” Gilbert said cheerily.

“No more head colds. No more stomach aches. No more trips to the doctor. No more nightmares, math quizzes, boring church sermons, liver and onions or squash.”

Gilbert laughed, but then Leatrice started thinking about all the good things she had left behind, such as her cats and her beautiful room at home, and she started to cry.

“I think it’s time to go back,” Gilbert said.

Leatrice began venturing outside the family crypt often, either with Gilbert or on her own. And then, on a beautiful Sunday afternoon in October, she saw them.

She recognized father’s automobile that he was so proud of, and then she saw who was riding inside: father, mother and her brother Reginald. She floated after the car—it wasn’t going very fast—and attached herself to the back of it.

Leatrice held on until father pulled the automobile into the driveway of the old house. She was happy to see that everything looked exactly the same. The first thing she did was to go around back and check on her kittens. They were all there and seemed healthy and happy, halfway on their way to being grown. She cried when she saw they recognized her. She longed to pick them up and nuzzle them against her face and hear their sweet purring.

Her room upstairs was the same. Everything was just as she left it, the books and pencils on her desk, the dolls and stuffed animals on the bed and the chair, the pictures on the wall, the lamp, the rocking chair, the clothes hanging neatly in the closet. Mother hadn’t changed a thing.

While mother, father and Reginald were having dinner in the dining room, Leatrice walked around the table, stopping and putting her hands on the back of each chair, experiencing the odd sensation of being in the same room with those closest to her in life and their not knowing it.

It felt good to be home, but she knew things could never be the same again. She could only observe life going on around her and not be a part of it. But still, wasn’t it better than nothing?

Since she dwelt in the spirit world, time, of course, didn’t exist. All time was the same. A minute was the same as an hour, a day the same as a year. In the time that was no time, her brother grew up, got a job in another state and left home. Mother and father grew old and frail. At ninety-one years, father died in his own bed and mother was left alone.

On winter evenings, while mother sat and read or knitted, or sometimes played the piano, Leatrice was nearby.

“I’m here, mother!” she said. “Don’t you see me? I want you to know you’re not alone!”

At times she was certain mother knew she was there but at other times she wasn’t so sure.

In the time that was no time, mother also died. The house was sold and all the furniture moved out. Another family took up residence, four children, two dogs and no cats.

She couldn’t stay in a house that was no longer hers, even if she was just a spirit, so she went back to the family crypt. Since time didn’t exist in the spirit world, cousin Gilbert and great-grandmother and the others didn’t realize she had been gone, although, in the world of the living it would have been decades.

There were additions to the family crypt, of course, in all that time that was no time. Mother and father were there with their own glows and they had a surprise for her: her cats were there, too—all the cats she had ever owned. Nothing else could have made her happier. She experienced a feeling of completeness, then, of going full circle and ending up back where she had always meant to be. Happy in life and now happy in death. She could never want anything more.

Copyright © 2018 by Allen Kopp