He Fell Over Dead

~ A Short Story by Allen Kopp ~

They lived on a small farm. They grew corn and wheat, strawberries, peaches, tomatoes, lettuce, eggplant, melons and cucumbers, among other things. Their chickens yielded four or five dozen eggs a week. They sold most of their eggs and whatever happened to be in season to two different stores in the town of Marburg twelve miles away. In the lush season, they set up a stand out in front of their property on the highway and sold whatever surplus they had to passing cars.

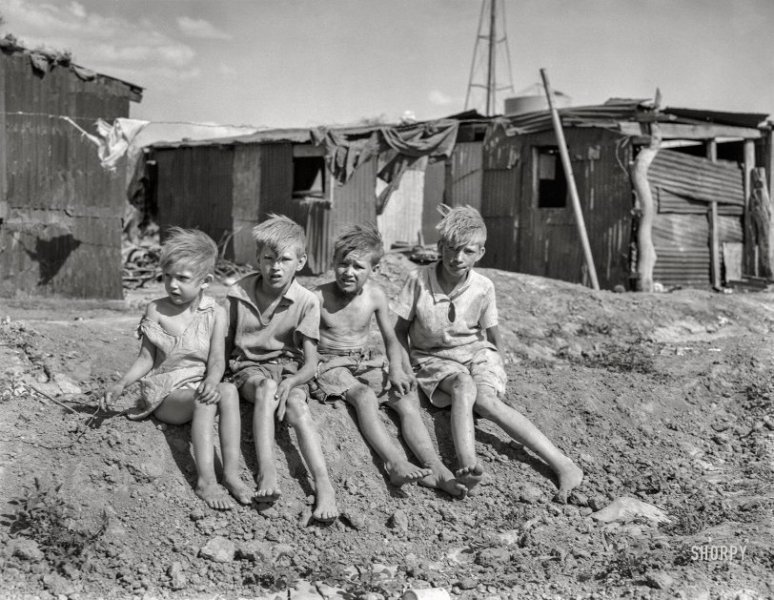

Lathrop was fifteen. He had gone to school through the eighth grade, and then he wasn’t obliged to go any farther. He wanted to go on to high school in Marburg but father said he was needed on the farm. Lathrop did the work of a hired hand without any pay. When he was younger, they had a hired hand, but his father fired him when he found he was stealing vegetables and selling them on his own in town.

Lathrop liked working at the vegetable stand. It was easy work in the shade of an enormous oak tree, and it gave him a chance to see and talk to other people, who were mostly friendly and cheerful. Sometimes somebody he knew from his school days would stop by and he would talk to them, but most of the people he had never seen before. They were just passing by on the highway on their way home from wherever they had been. They would see the stand, and the idea of fresh tomatoes, corn or cucumbers for supper would make them stop.

On a warm Tuesday afternoon in the middle of June, Mr. Wessel, the nearest neighbor, came by. He was happy to see that Lathrop still had a dozen eggs left and some tomatoes.

“How are you doing today, Lathrop?” Mr. Wessel asked as he counted out his money.

Lathrop felt flattered, somehow, that Mr. Wessel would speak to him in this way. Nobody else ever did. “I’m just dandy,” he said jauntily, with a smile. He put Mr. Wessel’s purchases in a wrinkled paper sack and handed the sack over the makeshift counter.

“Do you ever read books, Lathrop?” Mr. Wessel asked.

“I did when I was in school,” Lathrop said. He was reluctant to say that he lived in a house without books or that he had only gone through the eighth grade and would probably never go any farther.

“You seem like a smart boy. I have many, many books in my house. If you ever want to borrow, drop by and I’ll see if I have anything that might interest you.”

“Yes, sir! I’d like that!”

“You don’t have to call me ‘sir’. My first name is Eldridge, so you can see why people call me Wessel. It’s my handle.”

Lathrop smiled, even though he didn’t know what it meant. “I might just do that, sir,” he said. “Stop by and borrow a book, I mean.”

Late in the afternoon Lathrop was happy. He sold all the vegetables and eggs and had a cigar box full of change and one-dollar bills. He handed the money box over to mother.

“Mr. Wessel came by the stand today,” Lathrop said at the supper table. “He told me I could come over to his house and borrow some books to read.”

“You stay away from him!” father said.

“Why?”

“I don’t like him, that’s why!”

“If you don’t like him, does that mean I’m not supposed to like him, too?”

“If I find out you’ve been over there, I’ll knock your head off your shoulders and feed it to the hogs.”

After supper, when mother was clearing the table and father had gone outside, Lathrop asked her, “Why doesn’t he like Mr. Wessel?”

“He’s heard something about him, I guess,” mother said. “You know how he is.”

“What did he hear?”

“God only knows.”

“Well, I like Mr. Wessel. He’s nice to me. Most people don’t even look at me. I’m only Hodge’s kid and I don’t mean a damn thing.”

“I don’t like you to use that kind of language in the house.”

“Mother, when I was in school, I heard ten times worse than that every day.”

“I don’t want you to be like him.”

“Why did you ever marry him?”

“You never met my mother.”

She laughed then, something she hardly ever did, and Lathrop wiped the crumbs off the table onto the floor.

“I want to go back to school,” he said. “Eighth grade isn’t enough.”

“I know,” she said. “We’ll manage it somehow. And if you want to borrow books from Mr. Wessel, go ahead and do it. Just don’t let your paw find out. Keep the books hidden in your room.”

The next time father went to visit his ailing mother, a trip that always took all day, Lathrop, with his dog Ruff, walked the mile to Mr. Wessel’s house. His heart hammered in his chest as he knocked timidly at the door. He half-hoped that Mr. Wessel wouldn’t be at home.

Mr. Wessel came to the door and when he saw Lathrop he smiled and motioned him inside. Ruff settled himself on the porch for a nap.

“I hope I’m not bothering you,” Lathrop said.

“Not at all,” Mr. Wessel said. “I’m always glad of visitors.”

The house was cool and dark. Lathrop sat in a large padded chair across from the couch. Mr. Wessel sat on the couch and crossed his legs. He wasn’t wearing any shoes.

After some polite talk in which Mr. Wessel asked Lathrop about his family, his dog Ruff, where he went to school and other mundane things, he took Lathrop into the next room, his “study,” where he wrote and had his books.

Lathrop never saw so many books in one place before. There were shelves and shelves of books, so many books that the ones that wouldn’t fit on the shelves were stacked neatly in rows on the floor.

“Where did you get so many books?” Lathrop asked.

“Some are mine and some belonged to my family. When you’re the last one left alive, you get, by default, everything that belonged to everybody who came before.”

Lathrop wasn’t sure what Mr. Wessel was talking about, but he smiled and nodded his head.

Lathrop looked over the books. There were novels, volumes of poetry, short stories, books on history and books that people had written about their own lives.

“Do you have anything in mind that you’d like to read?” Mr. Wessel asked.

“I don’t know much about books,” Lathrop said. “In school, I only read what I had to to get by.”

“Have you ever read anything by Charles Dickens?”

“No. I’ve heard of him, though.”

“How about David Copperfield? Do you think you’d like to read that?”

“Sure, I guess so.”

“I read it when I was about you age. I don’t think you’ll have too much trouble with it.”

“Sure, I’d like to give it a try.”

With David Copperfield clutched tightly in his hands, he followed Mr. Wessel back into the front room. They sat again and after they had talked for a while Mr. Wessel got up and went into the kitchen and came back with two glasses of sweet cider and a little plate of walnut cookies.

After an hour or so, Lathrop realized he had been in Mr. Wessel’s house for over an hour. He would like to have stayed much longer, but he didn’t want to overstay his welcome. He thanked Mr. Wessel for David Copperfield and walked back home with Ruff trailing along behind.

He showed mother the book when he got home and inside the front cover where Mr. Wessel had written his name.

“That’s so you’ll remember who the book belongs to,” mother said.

He hid the book in the bottom of his dresser drawer. He couldn’t let father see it. He would be mad at him for disobeying orders to stay away from Mr. Wessel’s house and would make fun of him for reading such a story book.

That might after mother and father had gone to bed, he began reading David Copperfield in his bed. If father came and unexpectedly opened the door, which he never did, Lathrop could easily thrust it under the covers and pretend it wasn’t there.

He considered himself mostly ignorant and uneducated, but he didn’t have any trouble reading David Copperfield or knowing what was going on. There were some words he didn’t know and the characters talked in a funny way, but Lathrop knew it was just because they were in a different country and the book was written a long time ago.

The next time he worked the vegetable stand, he overhead two ladies from town talking as they picked out their vegetables. Lathrop didn’t care what they were saying, but when he realized they were talking about father he paid closer attention.

Lathrop gleaned from the ladies’ talk that father had a “girlfriend” in town and she had a small child by him. He paid the rent on the house she lived in and visited her regularly. The ladies had seen father, the woman and their child together at a fireworks display in the park on the Fourth of July.

“That old coot,” one of the ladies said. “He ought to be ashamed of himself. And she’s half his age, too.”

“She’s the one that ought to be ashamed,” the other lady said. “Damned old home wrecker!”

“Well, you never know about people.”

In a little over a week, Lathrop finished David Copperfield and was glad for a reason to make another trip to Mr. Wessel’s house.

Mr. Wessel asked Lathrop how he liked the book and Lathrop said he was surprised he was able to get through such a big book so fast and with seemingly so little effort. He forgot about the time when he was reading it.

Next Mr. Wessel gave him A Tale of Two Cities, which, he said, was a little more challenging than David Copperfield but of moderate length. Lathrop agreed to give it a try.

When the conversation switched from books to other matters, Lathrop told Mr. Wessel how he hated his father and was sure his father hated him. His father was gruff with him and impatient and turned his head away whenever Lathrop walked into a room. The two of them had very little to say to each other and never talked about anything that mattered.

He told Mr. Wessel his father didn’t want him to come there and borrow books but that he was doing it anyway when his father was away. His mother knew about it and thought it was all right. To Lathrop’s surprise, Mr. Wessel smiled and nodded his head.

“I never got along well with my father, either,” he said.

“What did you do about it?” Lathrop asked.

“Left home and didn’t come back until after he was dead.”

“What did you do away from home?”

“Went to college. Taught high school. Worked in a lumber mill and as a copy boy at a newspaper. I was clerk in a book store. I was even a waiter for about ten months.”

“Did you like that?”

“It made my legs tired.”

“Then what did you do?”

“When my mother died, I got a little money. Not enough to make me rich but enough to keep me from having to work, at least for a while.”

Then, even though he was embarrassed to say it, Lathrop told Mr. Wessel what he had heard the town ladies say at the vegetable stand.

“Do you think it’s true or just gossip?” Mr. Wessel asked.

“I think it could be true. He’s away from home a lot.”

“Does your mother know?”

“I don’t think so.”

Then there were other books: The House of Seven Gables, The Scarlet Pimpernel, The Sea Wolf, The Red Badge of Courage, Life on the Mississippi. There was a whole world in them that Lathrop didn’t know existed.

On a stifling afternoon in August, Lathrop was sitting in the wagon in the barn looking at an old newspaper he had found when his father came in. Ruff went to meet him, tail wagging, and Lathrop’s father kicked him. Ruff yelped and leaped out of the way.

“What did you do that for?” Lathrop said. “He only wants you to notice him.”

“I’m going to take him out and shoot him!” his father said.

“What?”

“I can’t stand that dog and I never could.”

“The only reason you can’t stand him is because he’s mine and you know I like him!”

His father wiped the sweat from his mouth with the back of his hand and grabbed Lathrop by the arm and pulled him off the wagon onto the floor.

“What’s the matter with you?” Lathrop said, trying to stand up.

“Yeah, what’s the matter with me? You’d like to know what’s the matter with me, wouldn’t you? The question is, what’s the matter with you?”

“I haven’t done anything!”

“You’ve been going over to that Wessel’s house. Don’t bother to lie about it because I know you have. What filthy things have you been up to with that man?”

“What?”

“What have you been up to with that Wessel?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about! He lends me books. I read them and then I take them back.”

“Yeah, and what do you do for him in return?”

“I don’t do anything!”

He grabbed Lathrop by the arms and turned him around and struck him on the side of the head with the flat of his hand.

“Let go of me, you bastard!”

“What did you just call me, you little chicken shit?”

Lathrop started to run and his father grabbed him from behind and slammed him to the floor. He was straddling him, undoing his belt to thrash him with it when Lathrop pulled himself up and started running again. He nearly ran into the wall of the barn and when he did he saw the big knife in the leather case his father used when he butchered hogs. He pulled the knife out of its case and when his father charged him he stabbed him in the throat. He then stabbed him two more times, once in the side of the neck and then just above the heart until he went down.

Right away Lathrop knew his father was dead. When he caught his breath, he took an old canvas tarpaulin and threw it over him so he wouldn’t have to look at him. Then he thought about all the blood that was leaking all over the floor of the barn that would be very difficult to clean up, so he wrapped his father in the canvas the best he could and pushed the body against the wall. Ruff jumped up and wagged his tail and seemed to think he was helping.

After he got himself a long drink of water, he went into the house and told mother what had happened. She dried her hands and sat down at the kitchen table and looked at him and didn’t say a word.

He thought about what he could do with his father’s body so that nobody would ever find it. Just burying it didn’t seem the right thing.

Two miles away was an old homestead that had been abandoned for seventy-five years or more, people said. There was an old well that went down two hundred feet, maybe three hundred. Lathrop remembered seeing it when he was seven years old. It had given him bad dreams for a long time.

After midnight, while mother was sleeping the sleep of the innocent, Lathrop went out to the barn and, without too much effort, pulled his father’s body, using ropes, into the back of the wagon. He then hitched the sleepy mule, the one they called Timmy, to the old wagon and set off into the woods along a road that could hardly be called that.

There was no moon. Lathrop could barely see past Timmy’s ears, but he found the old homestead from memory. He pulled the wagon around to the back of where the house once stood and jumped down. The well was right where he remembered it.

A metal plate covered the well. He was able to lift it by one corner and, with a huge amount of effort, slide it to the side far enough to drop a body in.

He pulled the wagon as close to the well as the remaining foundation of the old house would allow and, pulling on the ropes, maneuvered his father’s body to the opening and dropped it down, canvas and all. He listened for the body to hit bottom, but he heard nothing so he believed that meant the well was hopelessly deep.

He pushed the metal plate back into place and kicked the leaves and sticks that he had disturbed back so that the well would look undisturbed.

When he got back home, it was after three o’clock in the morning. He washed his hands and face and fell into bed, exhausted. He slept until nine o’clock and when he woke up breakfast was waiting for him in the kitchen.

For supper that day mother cooked fried chicken and mashed potatoes, Lathrop’s favorite. She baked a chocolate cake as a sort of celebration and put little red candy stars on top. It tasted so good that Lathrop ate almost half of it at one time.

In the evening it was rainy and cool and the dark came early, as if announcing the arrival of fall. Lathrop laid a fire in the front room, the first since April.

“You killed your father,” mother said, and it was the first words she had spoken about it.

“He was going to kill me.”

“Yes, but you killed him.”

“I couldn’t let him hurt Ruff.”

“You killed him.”

“We don’t need him. We can get along with him.”

“You killed your own father.”

“He got tired of farming and ran off to California or someplace even farther. He hated me and I’m pretty sure he hated you. He doesn’t want us to find him. Anybody who ever knew him could easily believe it of him.”

“I don’t know what to think of a boy who kills his father.”

“You’re as glad as I am that he’s gone.”

She looked at him in her quiet way and picked up her knitting and sat in her rocker near the fire. Lathrop lay on his back in front of the fire, a pillow from the couch underneath his head, and read a book. Ruff lay beside him. Now he could read all the books he wanted without having to hide. He was going to start to high school in September. It was a fine life.

Copyright © 2024 by Allen Kopp